You’ve probably never heard of Fabio Tagliolini. But if you’re a Ducati fan, then this is your God.

You’ve probably never heard of Fabio Tagliolini. But if you’re a Ducati fan, then this is your God.

Fabio didn’t waste time getting into motorcycles. He was born in 1920, grew up learning about things mechanical in his father’s workshop, and graduated from the University of Bologna as an engineer in 1943. His graduation thesis was on a method to bring poppet valves back to their seats without using springs.

Shortly after, he was drafted into the Italian armed forces, working as an aircraft and motorcycle mechanic.

He was wounded and sent home, and in 1950, he got a job with Mondial motorcycles, as a designer for their racing team – which dominated Grand Prix racing from 1949 to 1957.

Four years later, Ducati decided it would create a team of designers and engineers to make race bikes in order to improve the breed, and they head-hunted Fabio Taglioni to be their technical director.

They picked the right man.

Fabio Taglioni was not an easy character to work with. He did not accept discussion easily. His decisions were decisions, not opinions. He was a heavy smoker and a very temperamental man and, according to those who witnessed, his fits of anger were not something to be forgotten easily. But he was also a man with a passion. He was devoted to his work and his creations. And he loved racing.

Within six months, Fabio had built the first true Ducati race bike, the 100cc Gran Sport Marianna, which went on to win the Motogiro d’Italia, and the Milano-Taranto in 1955, 1956 and 1957.

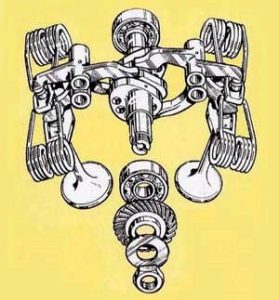

In 1957, he built Ducati’s first motor with Desmodromic heads.

The concept of ‘desmodromic’ was not his: in mechanics it has been known for centuries, and its appearance in the motorcycle and automobile fields dates back to the beginning of the 20th century, taking on all kinds of shapes. In the past, in fact, the chronic unreliability of springs (it’s strange to think back on manuals which recommended to those who were about to set off on motorcycle trips to keep spare springs handy… springs which were often located outside the engine in a position accessible for easy replacement) had pushed design engineers towards this system, thus leading to various interpretations.

The specific purpose of the desmodromic system is that of eliminating, at high speed, one of the greatest limits to the mechanical action of the valves. This happens when the springs are unable to act fast enough to close the valves. The basic idea of the desmo is that of replacing those annoying springs with a mechanical closing system similar to the one used to open them. By eliminating the springs, the result would have been a wonderfully fast-running motor. Well, this was the theory…In the world of motorcycling, years before Taglioni, many had attempted to successfully employ this system but no-one had succeeded.

Taglioni succeeded.

The 125 desmo’s first big race was the Swedish Grand Prix of 1956. It won, setting a new track record and lap record.

In 1959, Stan Hailwood commissioned a 250 desmo for his son, Mike. Taglioni basically put two 125 desmos side by side on the same crankcase. In 1960 the Hailwoods took it to England, and it recorded a fastest lap in its debut race at Silverstone.

By 1968, Fabio had a range of street motors ready, and Ducati released desmo 250, 350 and 450 sports bikes.

In March 1970, Fabio sketched a 90-degree V-twin. A desmo, of course. A 90-degree four-stroke twin is close to perfect in inertial balance, but hard to put in a motorcycle frame because it is so long.

By August he had a prototype motorcycle built. He used the famous Italian racer, Bruno Spaggiari, as one of the test riders. The next year, the GT750 was released at the Olympia Show in London.

Test riders loved it. Cycle Magazine wrote: “When the right foot peg glides perfectly on the asphalt at 80mph and the motorcycle never waivers even once, you know it was designed by a motorcyclist. And that he’s hit the mark.”

Ducati wanted to get back into racing, so Fabio built racing versions of the GT750. Two were entered in the first Imola 200 Miglia in 1972. They came in first and second.

In 1973, Ducati appointed a new manager, De Eccher. He scrapped all racing projects, and ceased production of the round crankcase 750s and all single cylinder models. Despite this, the 1973 Barcelona 24-hour race was won by Canellas and Grau on a round-case Ducati 750 SS converted into an 860 by the use of the Ducati 450 single sleeves and pistons.

De Eccher’s vision was to increase sales to America, and he had bikes built which he thought would appeal to American tastes. The crankcases of the now production 860 were squared off and looked nothing like those on the old 750. Giugiaro, who designed the crankcases, also designed two new motors for Ducati, the 350 and 500 vertical twins.

Fabio refused to have anything to do with them. In 1985, he retired.

Fabio Taglioni, and Ducati motorcycles with him, always remained faithful to a very distinctive philosophy. Even when the whole motorcycle world was going in the direction of bigger-heavier-wider-more-cylinders-more-power, his bikes remained light, thin, simple, and efficient. They had one or two cylinders and did not produce overwhelming power, but they were able to exploit every fraction of their horsepower to the best.

Fabio Taglioni, and Ducati motorcycles with him, always remained faithful to a very distinctive philosophy. Even when the whole motorcycle world was going in the direction of bigger-heavier-wider-more-cylinders-more-power, his bikes remained light, thin, simple, and efficient. They had one or two cylinders and did not produce overwhelming power, but they were able to exploit every fraction of their horsepower to the best.

For fifty years Ducati bikes followed the Taglioni philosophy: lightness and compactness opposed to the quest for sheer power; mechanical and combustion efficiency; modularity of components; an integrated bike, a low centre of gravity.

Fabio died in 2001. He was 80.

Ducati still makes desmos.

Words by Alan Moon