In 1970, the Willoughby District Motorcycle Club held the first Castrol Six Hour Production Race at Amaroo Park. The rules were simple. There was a Le Mans start. There were three classes: 250cc, 500cc and Unlimited. The bike had to be bog standard, except for handlebars, tyres and brake linings/pads. In the interests of safety. And all classes raced on the same track, at the same time.

The bikes were stripped by scrutineers after the race to make sure that they were standard.

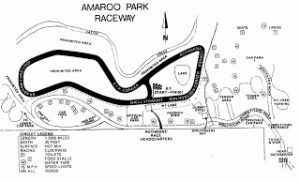

Amaroo Park was a bastard of a track. It was nestled in the hills at Annangrove, just off the road from Parramatta to Windsor, NSW.

Amaroo Park was a bastard of a track. It was nestled in the hills at Annangrove, just off the road from Parramatta to Windsor, NSW.

From the start, the track proceeded through a slight right, a slight left, up a hill, around a sweeper called Dunlop Loop (with no run-off areas), followed by a right hander, a sharp left (with no run-off areas), a short straight into Stop Corner (rock wall in lieu of run-off area), followed by another short straight which led into the right hander back to the start (cement wall in lieu of run-off area). It was only 1.9km in length. It was tight. And it was dangerous.

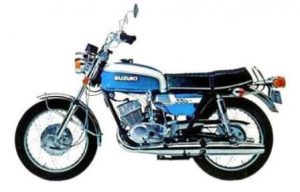

A young customs officer called Joe Eastmure had just started racing his BMW R60 a few years before. He upgraded to an R75, and then bought himself a Suzuki T250 twin two-stroke for 250 class production racing. In the inaugural race, he partnered another racer called Dave Burgess, and together they won the 250 class.

In the 1971 race, he partnered with Dave Burgess again, this time in the 500cc class on a Suzuki T350.

The T350 Suzuki was a T250 Suzuki with a bore job, and that was about the only difference. There wasn’t that much meat on the barrels, so the engine only displaced 315cc. If Suzuki had bothered to put a bigger drive chain on it, they may well have won the 500cc class in the 1971 Castrol 6 hour, but the cost accountants had their way and it came with a 525 chain.

The Eastmure/Burgess Suzuki was leading after three hours, and then it snapped its chain just outside the pits. Joe sat and watched the mechanics fitting a new chain with one eye and the passing bikes with the other. When he finally got back on the bike, he was angry, and he rode like a man possessed.

As he cooled down, he realised that he was making extremely good time, and passing a lot of bigger bikes. The Suzuki had ground clearance to spare, and Joe found he could keep his angry times up and ride very fast in a very calculated fashion. However, he’d lost nearly an hour, and he didn’t get a place.

But, he loved the bike, and for the next Six Hour in 1972, the Suzuki importers gave him a brand new T350 Suzuki. His previous partner Dave Burgess had accepted a ride on the new Kawasaki H2 750 two-stroke triple with Mike Steele, and Joe Eastmure decided he would ride the whole six hours himself.

Joe’s ride in the 1972 race was one of the most blistering rides in Australian production racing history. And also one of the most controversial.

It started badly.

Joe was running out of time to run the bike in. He had a lot of training to do. He did weights and running, and exercised with a hand squeezer. He lent the bike to a mate to put a few miles on it. His mate did, but forgot to fill the oil tank. And the bike seized.

They stripped the top end (an easy job on the T350). They bored it to first oversize. No problems, the rules allowed it as long as it was a standard part. And the mechanic noticed that the barrels and ports were misaligned, so he chamfered the bottom of the pistons by 1mm to bring the port timing back to standard.

They put it back together, put a few miles on it to loosen it up, and Joe fronted for a six-hour solo ride.

The T350 was geared pretty well perfectly for Amaroo, and Joe knew exactly how well he could take advantage of its enormous ground clearance. He could not take the bigger bikes on the straights, but on all but the slowest corners he hardly backed off the throttle at all.

It took an hour for Joe to get into the groove, after which he was lapping at just over 62 seconds. The outright lap record at Amaroo was just over 61. He did one lap at 61.4.

And he kept doing it. I was 15-years-old at the time, and remember watching the race on television. The big bikes would accelerate and brake, and it seemed that Joe Eastmure did neither.

After about the first hour, he had a comfortable lead on the rest of the 500 class runners, mainly Yamaha RD350s and Kawasaki H1 500s, but the big bikes in the Unlimited class were still in front.

There were two brand new 750s released that year having their Six Hour debut. The Kawasaki H2 was a three cylinder two-stroke with ordinary handling but a screaming banshee of an engine that made 74 horsepower. Its problem in the Six Hour was that it needed five fuel stops. The T350 could probably make it on three.

The Yamaha TX750 was a 750-twin four-stroke that was quite punchy, had good ground clearance, and made 63 horsepower. It was everything the Kawasaki H2 wasn’t. It was civilized. It had good fuel consumption. It even had counterbalance shafts in its engine to reduce vibration. Its problem was that its engine disintegrated after a couple of hours of racing. But it was a brand new model, and its riders were yet to find out about that.

Two-and-a-half hours into the race, Joe Eastmure took the outright lead.

He made it look easy. He would catch a big bike coming out of a corner, and slipstream it, getting towed to the next corner. There, the big bike would slow down, and Joe would make his passing move. He would hope to catch another big bike as he came out of the corner to repeat the “slipstream and slingshot” process. And he would hope that the riders in front of him stayed committed to their line, because there was no way Joe could have changed his. In this, he was lucky.

The Suzuki T350 had its fuel tap permanently on reserve, of course. It would do an hour-and-a-half on a tank at racing speeds. Joe took his last fuel stop at 2:30pm, and the race finished at four. He had to decide whether to pit for a quick splash to make sure he got home.

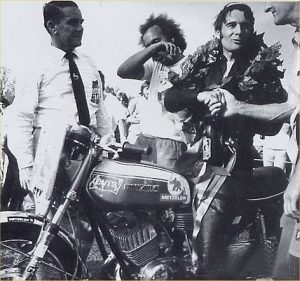

At ten to four, Mike Steele, riding the Burgess/Steele Kawasaki 750, closed in on Joe and passed him. Joe stayed on the Kawasaki’s tail and passed him back, and the crowd was treated to a memorable dice at the end of a memorable ride. Steele regained the lead, then at five to four went into Dunlop Loop too hard and dropped the Kawasaki.

Joe took the chequered flag five minutes later: 500cc class and outright winner. He had done 234 laps in six hours. His fuel tank was drier than one of my special martinis.

That night, while motorcyclists all over Australia were lifting glasses to a memorable ride, the scrutineers started stripping the bikes. And they didn’t like what they saw. Joe’s bike was missing its horn. And it pistons had been doctored. They figured that a missing horn meant that the bike was non-standard, and it would give a cooling advantage to a hot-running two stroke. And that standard pistons didn’t have a millimetre missing from the bottom.

So, they disqualified him.

There was much controversy and argument. There were arguments about fairness. Some said that the decision was political, that the club wanted to market the race as a Superbike race and couldn’t have a little 315cc two-stroke winning it. It was said that the Burgess/Steele Kawasaki was passed despite having two head gaskets on each cylinder to stop it pinging. It was said that another place-getter was passed despite not having a horn on his bike.

Joe copped it sweet. He entered the same bike in the 1973 Six Hour. The rules were more restrictive: you had to start the race with new footpegs, and the tyres had to be standard sizes, so his front tyre went from 3.5 inches to 3.00 inches. To make absolutely sure he was legal, Joe replaced the crank, barrels and pistons. And he made sure the horn was bolted on.

He won the 500cc class. He did 234 laps. Just like last year. But the Unlimited class had changed. The Z1 had arrived and nothing would ever be the same again.

Words by Alan Moon